How perpetual software licences are here to stay as firms avoid SaaS and snap up second hand bargains.

The Register FEATURE 26th September 2023: It can seem like the vast majority of the large software vendors these days are on a mission to shift their user base away from licensed, on-premise software to cloud hosted, software as a service (SaaS) subscriptions. But while that can make it easier for businesses to acquire the software in the first place via cheaper upfront purchasing costs, the longer term billing benefits appear to favour the vendor rather than the client.

It’s a situation, which appears to have created a thriving market for second hand and disused software licences that can deliver a more cost effective, long term ownership option for many organisations in the public and private sector.

Formed in 2004, Discount Licensing is a company that was set up specifically to sell discounted pre-owned Microsoft Volume Software in Europe. It buys up disused or surplus licences from organizations which may have reduced their headcount, migrated to more recent versions of the applications or indeed decided to lease the cloud-based subscription, then resells them at significantly discounted rates compared to conventional resellers.Discount Licensing’s unique Secondary Software Licence Centre (SSLC) is a web portal designed to provide its clients with complete transparency as to its origins and previous ownership.

It’s all in the TCO

Microsoft has been at the forefront of the SaaS transition, particularly when it comes to its flagship Office product suite, more recently rebranded as Microsoft 365. But as Noel Unwin, Managing Director at Discount Licensing, points out, Microsoft’s annual accounts and Eurostat data show that not everyone has moved to SaaS while perpetual licences still account for as much as 50 percent of software purchases in Europe. That suggests that perpetual on-premise Microsoft Office is not dead, he says, nor does it appear to be ‘scheduled for termination’ as the vendor and other cloud advocates would try to have us believe.

“Instead, we have seen this year that perpetual Microsoft Office has simply been ‘rebranded’ together with Microsoft’s cloud Office 365 sister product under the guise of Microsoft 365.”

While there are many different reasons why a company might not want to switch to a cloud subscription model for their software, cost is probably at the top of the list for most. Unwin estimates that the average migration lifecycle from a previous on-prem version to a more recent is around six to nine years. That means a company that was using Office 2013 probably won’t upgrade until 2021, and the cost of leasing that subscription over the interim nine year period, vastly exceeds what the same organisation would have paid for an equivalent perpetual licence for the same or similar products.

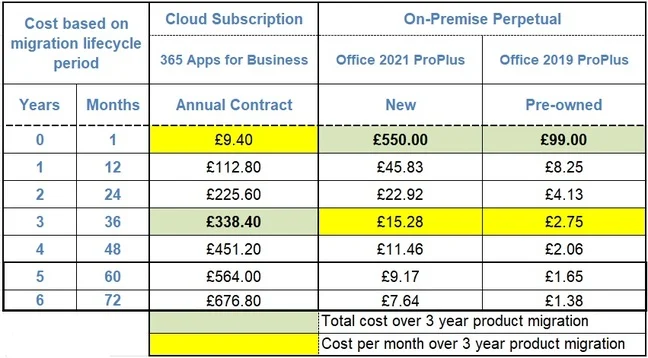

As displayed in the table below, Discount Licensing’s calculations suggest that the total cost of owning Microsoft 365 Apps for Enterprise over a six year period would be £676.80 for example, which is 23 percent more expensive than the cost of a perpetual licence for Office 2021 ProPlus purchased from new (£550). Yet at the same time, purchasing an earlier pre-owned version of Office ProPlus (2019) would be no more than £99 estimates Discount Licensing, which results in a considerable saving.

“If you have a look at the cloud cost over nine years, as opposed to buying an upfront perpetual licence, it is staggering,” says Unwin. “You’ll be paying six to nine times as much. Companies, whom can afford the upfront cost, won’t be told to rent something when it will end up costing them more money in the long run.”

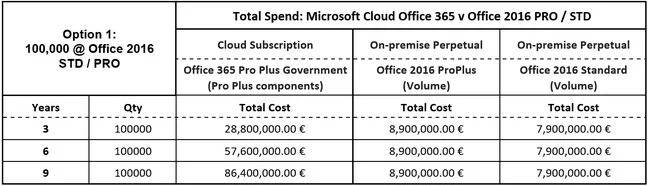

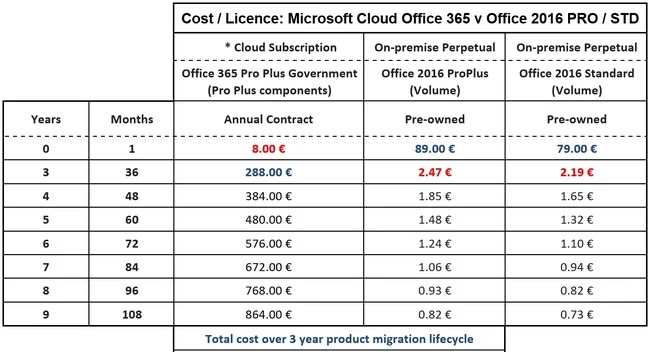

An example of just how much can be saved came from a large public sector organisation in France. This state owned company employs over 250,000 staff and has a turnover in excess of €40bn. In 2020, it performed a U-turn on its original plan to migrate 100 percent to the Cloud Office 365, and instead purchased 100,000 pre-owned Office 2016 licences. As the following table(s) indicate, its decision to move back to perpetual pre-owned software, rather move fully to Cloud 365, saved the French taxpayer approximately €49m over the projected 6 year migration period (the period of time that it’s expected to remain on the 2016 version) reckons Discount Licensing.

While Discount Licensing trades primarily in Office licences, it handles other Microsoft application and server software. These too have seen recent changes which sometimes make it more cost effective for companies to use older, licenced versions of the software. Since Microsoft changed the user rights in 2022 for example, SQL Server has required active software assurance to run on virtual machines (VMs) explains Discount Licensing sales manager Mick Shotton, which is a particular problem for smaller businesses.

“They buy SQL Server for VMs, but just run it on a small scale, and all of a sudden their costs have gone up considerably,” says Shotton. “And there are older versions of SQL Server they can use without these licensing restrictions.”

Stability, simplicity and flexibility play their part

Nor is cost the only reason why IT departments might not want to migrate to the latest version of Microsoft 365. Many organisations are happy with the tools and features in the applications they already have, and are in no hurry to perform a refresh or upgrade. That’s sometimes just because they use a smaller subset of the applications, tools, features and capabilities supplied which render an older version of the software better aligned with their requirements.

Stability is another factor, particularly where the company uses proprietary or bespoke applications, which have been developed in-house to integrate with Office tools – a working relationship that risks disruption when new features and functions are installed through regular updates.

“We’ve had a hotel chain that spent an awful lot of money on a booking system but it wouldn’t work with anything new in Office 16,” recalls Shotton. “So they had to keep buying old Office licences. Buying the current version was quite a costly way of doing things, so pre-owned software was a very cost effective solution for them until they could get the money in their budget to update their booking system.”

Proof of ownership eaid to compliance

Irrespective of whether their licences are purchased new from the vendor or on the second hand market, companies still have to prove ownership of the software – to show documentation that confirms the previous owner is no longer using the software or the licence, and that the licence has been transferred to a new owner. To that end Discount Licensing is ISO9001 certified and provides proof of ownership for every purchase and sale in line with the European Software Directive 2009/24/EC, which was ratified to protect the copyright of computer programs in EU member states. Not only that, it also provides the documentation that will satisfy a Microsoft audit should the software company ever come calling.This documentation too is provided to clients via Discount Licensing’s SSLC web portal.

Ian Nicholls is Director and managing consultant at the SAM Club, an independent licensing and software asset management company, which works with Discount Licensing and helps organisations manage and optimise the purchase, deployment, maintenance, utilization and disposal of their software applications.

“One of our clients, we actually purchased their pre-owned licences back in 2015, and about six months later, they were audited by Microsoft,” said Nicholls. “They got through the audit without any problems as we could show proof of payment and the ownership had been transferred with the documentation provided. Plus that the pre-owned software was first put to use within the EU or UK and a confirmation that the software was no longer used by the previous company.”

Local regulation has another part to play in regions of the world. On August 31st this year for example, Microsoft announced to changes to its O365 and Microsoft 365 packages which will see them sold without Teams included for a slightly reduced fee in the European Economic Area and Switzerland following European Commission competition concerns. This is exactly the sort of unbundling which could prompt some customers to reassess the way they pay for Office in the future, says Nicholls, as access to the cloud-based conferencing and collaboration app enticed some businesses onto the SaaS platform initially.

Elsewhere, organisations in other vertical sectors, such as education, are sometimes hindered from moving applications into the cloud due to rules on data privacy and collection. Discount Licensing has clients in the legal sector too which it describes as “very risk averse that want to make sure anything they deal with is 100 percent legitimate and not going to cause any issues”.

Personal preference and distrust of global corporations for whatever reason can also play their part. There are always customers that “just don’t like Microsoft and would rather not deal with them” says Shotton, a segment of the market for which Discount Licensing provides a competitive, more flexible option.

“That’s how we come in because we try and advise them and give them a more cost effective solution,” he explains. “We’re also more prepared to negotiate [on price]. If a client wants to do something cost effectively and the current [Microsoft pricing] rules don’t allow it, we can always say ‘well, have you considered this?'”.

The future involves perpetual

If the shift to SaaS continues at another 5 percent a year for the next ten years, then perpetual could conceivably disappear completely by 2033 according to Discount Licensing’s forecast. But that’s unlikely to happen, not least because there is also evidence that Microsoft and other software vendors will increasingly embrace a hybrid licensing model that involves a more equal mix of both types of billing, with applications like Office staying on prem and others making better sense in the cloud.

“I think they’ve reached the point where they can’t deny it anymore,” says Unwin. “So rather than just saying everything’s going to the cloud, maybe it’s a better solution to have a hybrid part cloud and part perpetual offering – there’s no one solutions fit all in the world of software”.

“Businesses are seeing the cost of cloud subscriptions increasing, so consideration towards hybrid models to try and save money should always be considered,” added Nicholls.

A good example of the enterprise software licensing model, which could eventually bed down can already be seen in the gaming industry, where Microsoft has made significant investments in the last few years. On the one hand the software company makes certain games available under its Game Pass subscription service. But it also allows individual titles to be purchased directly for a one off fee. And at the end of the day, Microsoft is extremely unlikely to “turn off the tap” on a revenue stream which still makes it billions of dollars every year.

Unwin estimates that cloud or SaaS subscriptions made up around 5 percent of the commercial spend for Microsoft in 2014, with Office representing the bulk of the total. Nearly ten years on, Microsoft still doesn’t separate perpetual and cloud software revenue, but it does earn around $63bn from what it terms productivity and business processes which span both sources of income. With Eurostat numbers on cloud adoption suggesting that enterprise adoption of cloud services was around 41 percent as of 2021, that suggests the company could still be making as much as $37bn out of perpetual licences, Unwin reckons. And that’s way too much money for even Microsoft to ignore even if cloud adoption has risen to as much as 50 percent by 2023.

For any enquiries about Microsoft software licences, simply complete the Contact Form. A member of our team will respond to your enquiry within 24 hours.

Image Source: Unsplash